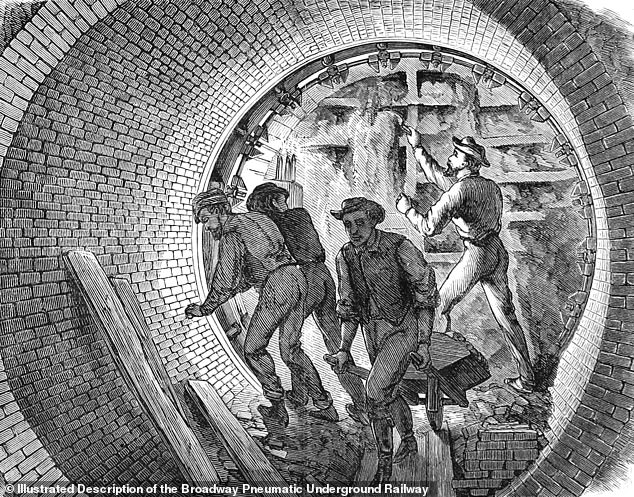

Beneath the darkness of night, 20 feet underground, workers dug an eight-foot-wide, 300-foot-long passage in the heart of the city.New York City.

They spent many months working behind the scenes, and upon its unveiling, the outcome resembled a tale from a Jules Verne novel.

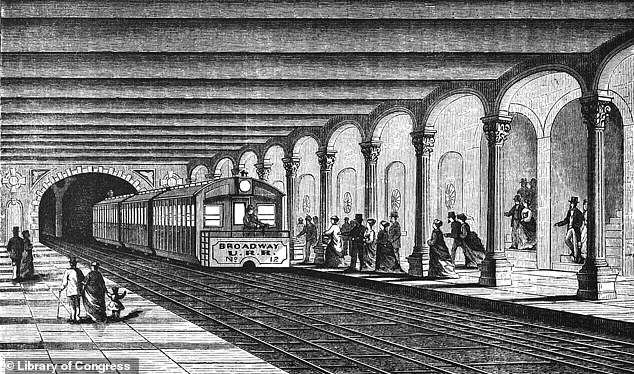

Sleek, efficient, and opulent - featuring sofas and even a grand piano and a fountain filled with goldfish - it aimed to revolutionize the future of public transportation not only in Manhattan but globally.

Nevertheless, political influences and favoritism undermined the initiative before it could evolve beyond being merely an oddity.

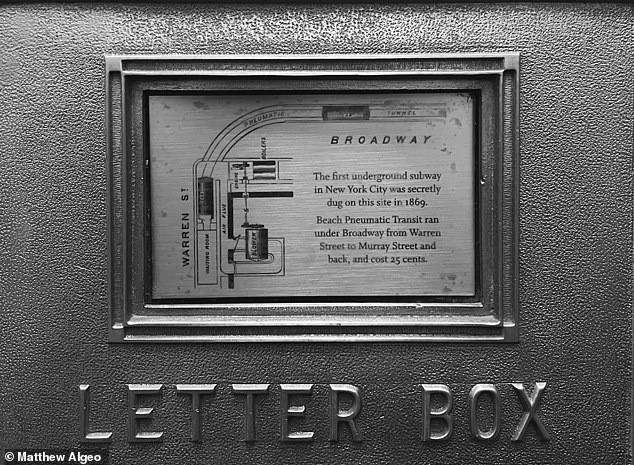

Now – 155 years later – it is nearly forgotten, indicated only by a small brass plate in a residential building in the city.

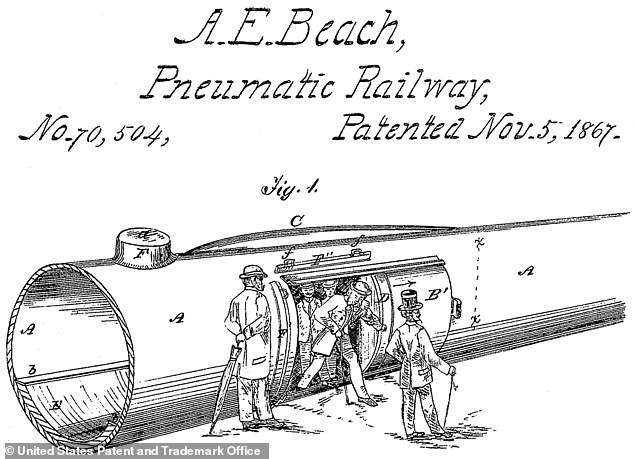

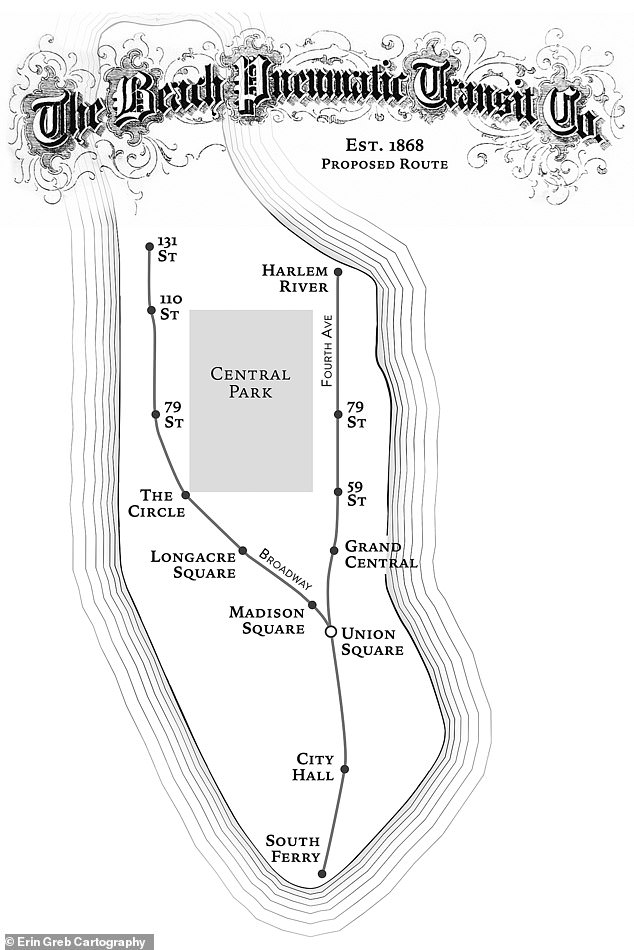

The secret passage was conceived by the eccentric inventor Alfred Beach, whose aspiration was to construct a pneumatic tube subway spanning the entire length of Manhattan.

In addition to being the publisher of Scientific American, Beach was also a dedicated supporter of American inventors and had his own inventions.

Therefore, during the winter of 1869–70, he invested his personal wealth to demonstrate the idea – a section of pneumatic subway that, if endorsed by city officials, would ultimately extend along the entire length of Broadway, from the Battery to the Harlem River.

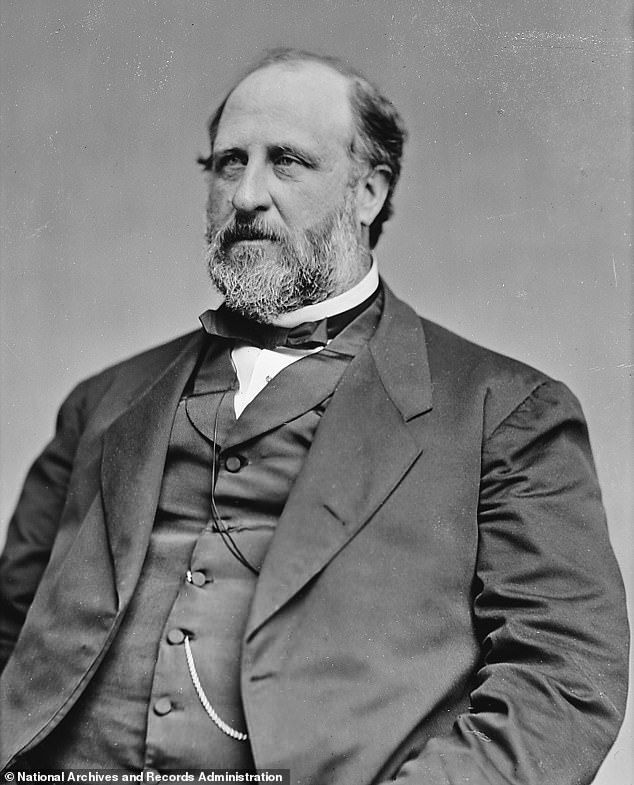

Beach conducted his project in secrecy, aware that the city's infamous political figure, William M Tweed, would never approve its construction openly.

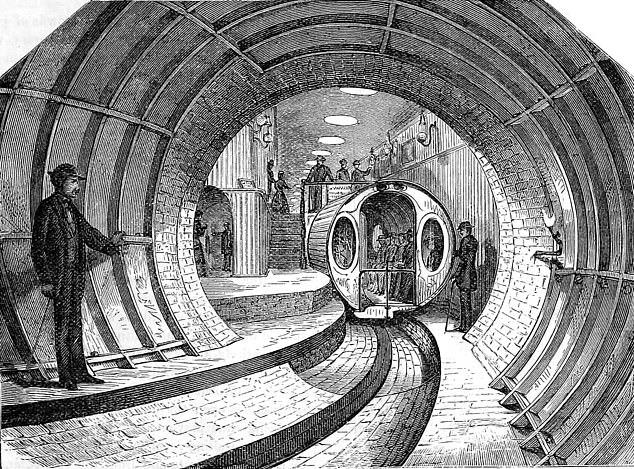

A massive fan pushed a cylindrical train carriage along the tunnel and pulled it back.

As no steam engine was needed, the tunnel did not become filled with harmful smoke and debris, unlike those on theLondon Underground did.

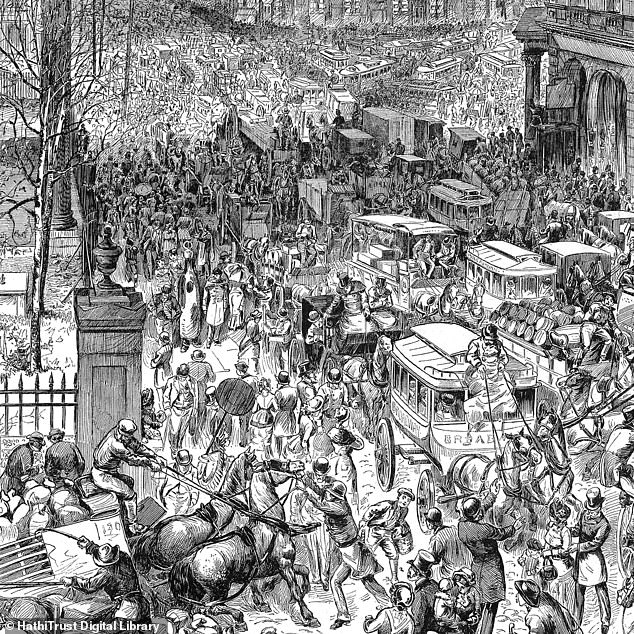

As there were no horses involved, travelers didn't need to concern themselves with stepping in horse manure, a common problem on the streets, where each of the city's 10,000 working horses produced 30 pounds of waste (and four gallons of urine) daily.

Located in the basement of a clothing shop on 260 Broadway, the waiting area—America's initial subway station—was designed in line with the Gilded Age, featuring luxurious sofas and artwork adorning the walls.

There was also a distinct lounge set aside for women. A visitor described it as 'a sort of Aladdin’s cave'.

However, the horse-drawn streetcar and stagecoach operators would not accept this underground intruder. They had a monopoly over public transport in New York and provided significant funds to Boss Tweed and his Tammany Hall associates to maintain their dominance.

Beach probably invested around $300,000 of his personal funds—half of his total wealth—into the project. However, after opening the initial block-long section of the Beach Pneumatic Railway, he was confident that the public would support it—and would mobilize to pressure Tweed into agreeing to finish it.

Subsequently, Beach would lengthen the tunnel along Broadway, swiftly transporting passengers up and down the island at a maximum speed of 60 miles per hour, an unprecedented velocity during an era when a horse-drawn carriage journey from City Hall to Central Park could last for hours.

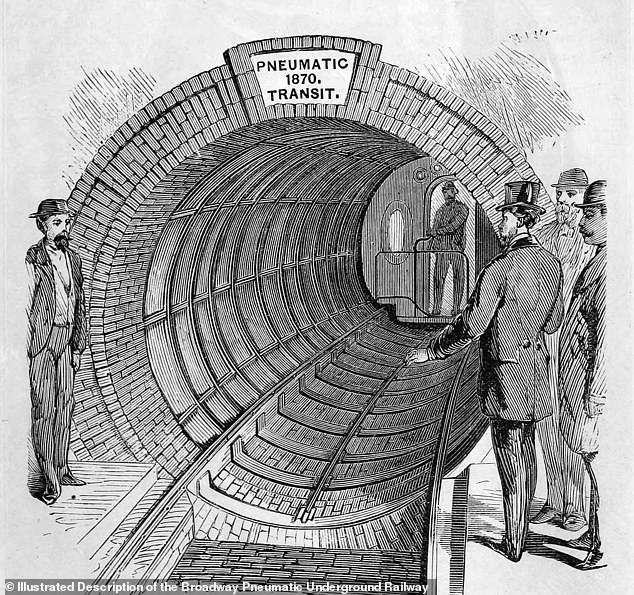

On the Saturday afternoon of February 26, 1870, Beach unveiled the entrance to his concealed subterranean pneumatic railway.

Surprised New Yorkers discovered that their city was home to the first underground railway in the United States and the second in the entire world, following London's. They rushed to the opulent station located beneath the intersection of Broadway and Warren.

They paid 25 cents to board the carriage and be propelled down the street before being pulled back. Beach contributed the earnings to an orphanage.

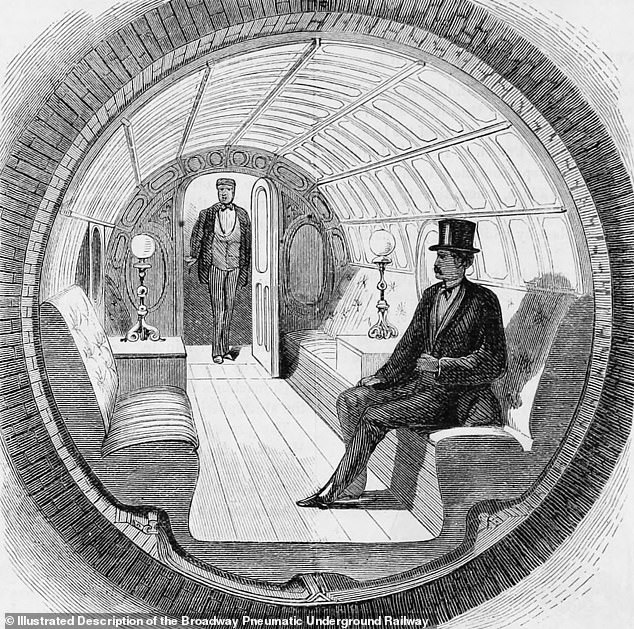

The carriage was elegantly decorated, featuring zirconia lights and cushioned seats. Riding Beach’s subway was unlike straphanging nowadays. This was a sophisticated journey.

Taking your seat," noted the author and social activist Helen Stuart Campbell following her visit to the tunnel, "with the doors at both ends shut, the engineer or conductor presses a telegraph wire located on the tunnel's wall.

A short while later, the vehicle starts moving, yet so smoothly that you barely realize it, until the conductor announces, "Murray Street!" upon opening the door, and in a blink, you find yourself back at the initial location on Warren Street.

And what caused it? Not steam or horses, but air by itself.

Alfred Beach was right: The general public became enamored with his small pneumatic railway.

Equipped with petitions gathered from thousands of people, the inventor traveled to Albany to seek approval from the state legislature to expand his tube.

In 1871 and 1872, the legislative body enacted laws providing him with a charter, but each was rejected by Democratic governor John Hoffman, who had secured his position through Tweed's influence.

When the Tweed Ring eventually collapsed - with leaked documents revealing the leader had diverted millions of city funds into his personal account - it finally opened the door for Beach to secure his charter.

In April 1873, the newly elected Republican governor, John Adams Dix, gave his approval, but the timing was extremely unfortunate.

In that spring, Jay Gould's plan to dominate the gold market failed, leading to a severe economic crisis commonly referred to as the Panic of 1873.

Indeed, it was a severe economic downturn. Credit vanished, leaving Beach unable to secure financial support for his unrealistic transportation project, and the concept eventually faded away. The tunnel was repurposed as a shooting range, where events were organized by a group that had recently been established in New York: the National Rifle Association.

Eventually, it suffered from neglect and the entrance was sealed off, a tightly closed remnant of a time when it appeared the future of public transport would rely on pneumatic systems.

Beach passed away on January 1, 1896, feeling let down but not resentful about the failure of his once-forgotten pneumatic subway (even though his family members today still regret his choice to invest all his money into it).

Just under three years later, on Sunday, December 4, 1898, the structure located at 260 Broadway, where Alfred Beach had previously introduced his pneumatic railway 29 years prior, was destroyed in a puzzling fire.

Two police officers on patrol near City Hall first observed fire emerging from the building's basement around 10pm that evening.

Firefighters reached the scene in under five minutes, but by 10:30 PM, the building had become just a 'burning skeleton'.

The reason behind the fire remained unknown.

The fire started in the building's basement - where 'a type of Aladdin’s cave' had once welcomed guests to the Beach Pneumatic Railway.

However, any remnants of the opulent lounge that may have still existed were erased when the structure collapsed in on itself. It took several months to remove the debris.

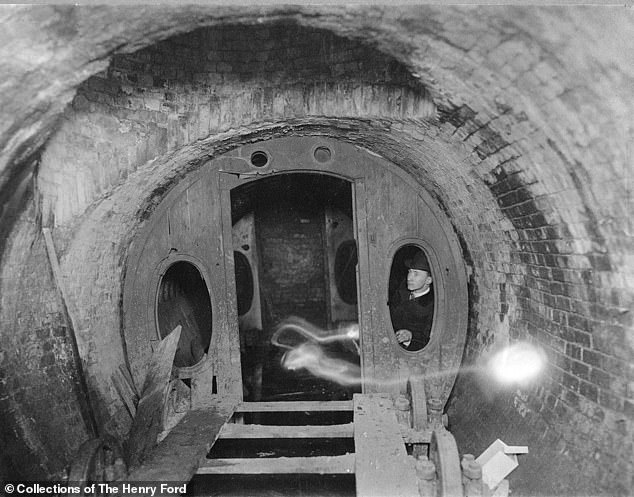

The following April, cleanup workers eventually arrived at the basement, where they found a brick wall beneath the pavement. After breaking through it, they uncovered the old Beach tunnel. At the far end stood the carriage, which had once been beautifully furnished, but was now decaying.

"I was standing in one of the cars a few days ago, which was once a luxurious compartment more than a quarter of a century ago, covered in upholstery, bright with lights, and moved silently under Broadway," said a reporter who visited the location.

Passengers remained seated in comfortable cushions and gazed through the oval windows as the vehicle smoothly moved through the tunnel with white walls, powered by a novel energy.

The journalist referred to the worn-out carriage as a 'magic-filled coach more enchanting than one created by Cinderella's fairy godmother'.

The uncovering of the hidden tunnel beneath Broadway triggered a surge of longing for the old 'Tweed era,' yet real estate growth in New York remains indifferent, and by the end of 1899, the tunnel's access had been sealed once more, with the start of a new structure on the southwest corner of Broadway and Warren Street.

That structure, currently labeled as 258, remains standing today. It is now a cooperative housing complex, with apartments available for purchase at $1.5 million.

A subway line would not commence operations beneath Lower Broadway until Saturday, January 5, 1918, approximately 50 years following Alfred Beach's establishment of the Beach Pneumatic Transit Company.

While the construction was ongoing, the old Beach tunnel was rediscovered. At this point, the old wooden passenger car had nearly entirely decayed.

Each sign of the Beach tunnel was later demolished to accommodate the City Hall subway station, whose platform now measures 535 feet in length – over 200 feet longer than the original tunnel.

I couldn't locate any tangible evidence of the Beach Pneumatic Railway. The sole indication is a small brass plaque mounted on the letter box in the lobby of 258 Broadway, above the location that once housed the grand waiting room.

It states: "The initial subterranean railway in New York City was covertly constructed at this location in 1869. The Beach Pneumatic Transit operated beneath Broadway from Warren Street to Murray Street and returned, with a fare of 25 cents."

To view the plaque, you will need to request access from one of the building's occupants.

The Hidden Subway of New York: The Innovative Vision of Alfred Beach and the Beginnings of Public Transport byMatthew Algeo is released by Island Press on September 30

Read more- What surprising discovery did an MTA employee make through a single taste, within the water-drenched tunnel in New York?

- Understanding the Tube: In what ways do the enigmatic 'Labyrinth' signs celebrate 160 years of London's Underground heritage?

- How did a train filled with New Yorkers come together to stop a crab-filled disaster?

- What caused a young boy to become entangled in the dangerous excitement of subway surfing, resulting in his fatal accident?

- How did London's hidden tunnels transform from WWII shelters into an appealing travel attraction?